After I studied Buddhism seriously and critically, it happens that many things taught by the tradition have to be discarded. I do not want to make myself in trouble by rejecting the tradition. But rather my integrity does not allow inconsistency (which probably leads to hypocrisy). When we really understand things critically, we cannot help rejecting things not conforming to what we hold as true.

Still, many things in Buddhism survive the bomb of critical thinking, and we can apply them to our contemporary life. Here I will show the most realistic use of Buddhism that has withstood tests for more than two millennia. But to make it applicable to the world today, we have to interpret it with new light.

As the big picture tells us, Buddhism emerged into the world to solve the problem of suffering. The main question the Buddha tried to answer was how to do away with suffering and be happy. And the solution is not the doing upon the world, but to make ourselves more capable to be happy. To develop oneself is the key to be happy, so to speak.

That may sound familiar to those who know the ethics of Aristotle. In short, we have to train ourselves until we possess dispositions that make us happy. Scholars generally call this system virtue ethics. And many see Buddhism in the same way, but with its own framework.

What I will describe here goes beyond the notion of ethics in its narrow sense—what kind of conduct counted as good. But rather it represents the whole guideline of living a wholesome life according to the Buddhist model.

It is worth noting that, the wholesome life in Buddhist view is not achieved by having or getting rid of things, or by doing a particular set of actions. Rather, the wholesome life is attained only by training or developing oneself. There are many instances in the canon confirming this, as shown below:

Cittassa damatho sādhu, cittaṃ dantaṃ sukhāvahaṃ. (Dhp 3.35)

The mastery of mind is good. The trained mind brings happiness.

Attanā hi sudantena, nāthaṃ labhati dullabhaṃ. (Dhp 12.160)

With oneself well-trained, [one] gets a guardian hard to obtain.

[So] Danto seṭṭho manussesu, yotivākyaṃ titikkhati. (Dhp 23.321)

Which person endures [insulting] words, [that one], trained [oneself], is the best among humans. (my translation)

The threefold training: the big picture

The threefold learning is the backbone of Buddhist training (sikkhā), commonly known as the triad sīla (morality), samādhi (concentration), and paññā (wisdom). The general idea is simple: Embarking on the Buddhist way of living, one must learn (a) to behave properly or be moral, (b) to concentrate the mind, and (c) to be wise.

The general idea is so vague that applying these to the real life looks indistinct from the general good way of living. Unquestionably, one has to be ethical according to the social standard, and to be wise is far better than to be foolish. Concentration sounds a little unique, but it can mean the opposite of ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder), which normal, healthy people have.

To understand the training in the Buddhist way, we have to trace its origin first. Surprisingly, there are scanty details on the subject. Mostly they are just mentioned by each name, without any further explanation. An important instance can be found in Mahāparinibbānasutta.

iti sīlaṃ, iti samādhi, iti paññā. Sīlaparibhāvito samādhi mahapphalo hoti mahānisaṃso. Samādhiparibhāvitā paññā mahapphalā hoti mahānisaṃsā. Paññāparibhāvitaṃ cittaṃ sammadeva āsavehi vimuccati, seyyathidaṃ – kāmāsavā, bhavāsavā, avijjāsavā. (D2 142, DN 16)

Thus morality, thus concentration, thus wisdom. Trained by morality, concentration is rich in fruit, rich in benefit. Trained by concentration, wisdom is rich in fruit, rich in benefit. Trained by wisdom, the mind is liberated completely from mental intoxicants, namely the intoxicant of pleasure, of existence, of ignorance. (my translation)

In other places, adhisīlasikkhā, adhicittasikkhā, and adhipaññāsikkhā are mentioned. Here, citta is used instead of samādhi. In this context, it means mental capacity; more or less both are synonymous.

In Aṅguttaranikāya, specific explanations are also given. By and large, adhisīlasikkhā means the rules of monks to be learned, adhicittasikkhā means the four jhānas, and adhipaññāsikkhā means the penetration of the ultimate truth. I find these specific explanations have little use for us. So, I ignore them and do not try to explain further.

I am not sure why adhi is added here. Thus, these can be rendered as higher morality, higher mentality, and higher wisdom. In what sense of higher, I still wonder. Perhaps, it means higher than worldly concerns, hence super-mundane (lokuttara). Since the adhi-things sounds too discriminating, we will stick to the simpler terms: sīla, samādhi, and paññā.

The most elaborate exposition of the threefold training is Visuddhimagga of Buddhaghosa. He structured the whole treatise upon this model. We will not go that way, because this will be another instance of Buddhist commentaries. So, those who want know it in the traditional way, please consult Visuddhimagga directly. Here, I will make it simpler and applicable to our contemporary life.

The passage given above depicts a linear relationship among the three and the liberation: morality > concentration > wisdom > liberation. This means you have to be well-trained in morality first so that you can get the concentration right. Likewise, you have to be well-trained in meditation first so that you can have wisdom. With this wisdom, you can get liberated.

This linear model is impractical, misleading, and useless. This misunderstanding makes many people, monks included, see that liberation is impossible because they think they cannot fulfill the morality to make viable concentration happen, and consequently they think wisdom is out of reach because they by no means can get the right concentration.

This hopelessness also makes monastic business thrives. Since no one can get things right, so we should do only the givings (dāna) just to ensure good life in the future. This line of thought makes barren the threefold training and makes Buddhism irrelevant to the modern world.

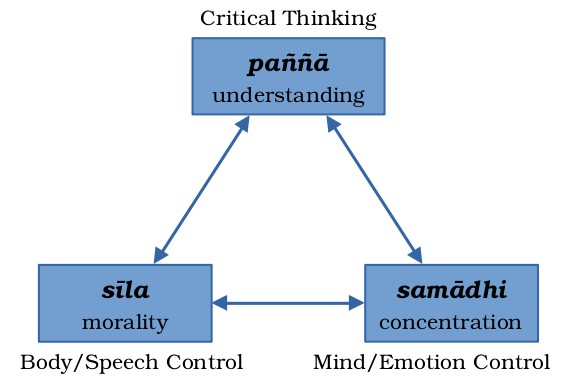

Figure 1: Triangular model of the threefold training

So, I make the model triangle instead, as shown in Figure 1. The triangular relations show that each fold of training depends on one another. I use understanding instead of wisdom to make it less esoteric. I also leave out liberation from the relationship because it is redundant and likely to make us result-oriented in practice, which hampers the very result of it.

To make the model more applicable, I attribute understanding to critical thinking. This makes understanding not just the result of the other two, rather it is an active component that we have to use it. So, understanding exactly means doing critical thinking in a right way.

Likewise, morality exactly means controlling your body and speech to do and say the right things. And concentration means controlling or mastering your mind.

On the part of morality, if we take it strictly, it can draw the whole subject of Buddhist ethics into consideration. That is too much. We can think it simply in this way: actions counted as good in Buddhism are those not coming from greed (lobha), anger (dosa), and delusion (moha).

On the part of concentration, I means meditation done in a simple way. You do not need to practice deep meditation in this model of development. So, everyone can do it. The main purpose of meditation is to get better control of your mind and emotions.

By this account, morality and concentration are combined into self-control development. This development is important to prosperity of our life. If you can control yourself well at young ages, you are likely to be successful in all aspect of your life, so to speak. On the contrary, if you cannot control yourself well, you are likely to be controlled and manipulated by others.

Self-control is also the essential complement to critical thinking, because reasoning alone cannot change our life. For example, we all have many good reasons that smoking is bad to our health and social relations, still some cannot make themselves quit because they lack self-control. To quit smoking, one has to make a resolution and new habit in the same way that we practice meditation.

I will wrap up this section by showing how the three parts of training link together using this scenario. You are walking in a street. Somebody, unknown to you, approaches and scolds you with harsh words. In this situation, untrained persons will get angry and may do harm to that guy. But if you can control your emotion, you will not get angry easily, and you can control your body and speech not to harm him in turn, physically and verbally. By not getting mad, you can think over it critically, and you may realize that it is unusual that someone will scold a stranger. So, the guy may have a mental problem or he is just a part of a candid camera ploy. After you are aware of what is really going on, you can take action or response more properly. Or by thinking like this first, you will not get angry at the guy. Instead, you may feel more sympathetic to him.

As the scenario shows, each fold of the training has to be trained hand in hand. You cannot put one fold aside and focus only the one you feel comfortable with. This is the heart of Buddhist way of training.

The noble eightfold path: model for enlightened beings

When the threefold training is described, the noble eightfold path is often drawn into perspective. This can give us a more concrete picture of the model, shown in the Table 1.

Table 1: The noble eightfold path and the threefold training

1. Right view

2. Right intention |

Wisdom/Understanding |

3. Right speech

4. Right action

5. Right livelihood |

Morality |

6. Right effort

7. Right mindfulness

8. Right concentration |

Concentration |

There are plenty of explanations about the noble eightfold path you can find. Most of them are parochial, and ideology-oriented, even in the canon itself. For example, right view is explained as the view corresponding to the four noble truths. So, what is ‘right’ here means ‘complying with’ the system, which is often problematic when looked closely/critically.

To make it more applicable, only the general idea of each element is used here. So, I give my own explanation as follows:

- Right view is the very product of critical thinking. Before that, you must have an intention to find the truth or understand things as they really are (not just as authority tells), or to make our and other life better. Right view will be never obtained by adopting certain beliefs without considering them critically first.

- Right speech, action, and livelihood can be lumped together, meaning good conduct. As mentioned earlier, in terms of Buddhism ‘good’ means void of greed, anger, and delusion.

- Right effort means the effort to make the other factors happen. It means commitment, determination, and perseverance. By this rendition, the right effort is not applied only for concentration, as the tradition puts it. It should be seen as the driving power of the whole training.

- Right mindfulness is the mindfulness used under the presence of the other factors. So, a mindful killing is not counted as ‘right’ here. By this account, therefore mindfulness is not bound exclusively to concentration as the tradition sees. Mindfulness is necessary to every aspect of the training.

- Right concentration is obtained by meditation that can do away or lessen greed, anger, and delusion. Other kind of meditation that cannot do this, or even strengthens the three, is not counted here.

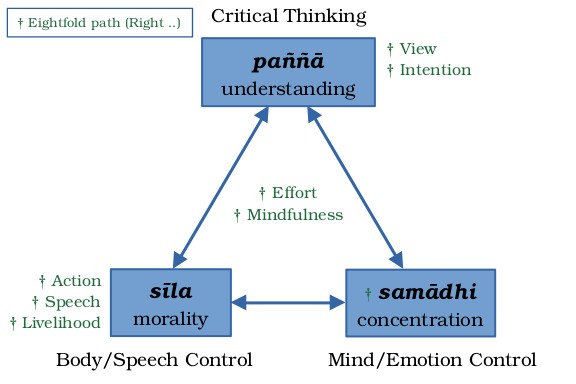

By my account given above, our triangular model of the threefold training can be elaborated as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: The triangular model with the noble eightfold path

Does the noble eightfold path have things to do with liberation? As asserted by the Buddha himself, the eightfold path is the way to get enlightened. Is my simplified account able to do the job—or is just that simple?

Surely it does, because I see no substantial contradiction between the traditional explanation and my account. I just make the model more applicable. So, it should lead you to liberation. A more serious question, however, is what you exactly mean by liberation or enlightenment. I will not go to this metaphysical problem.

I suggest instead that those who lead themselves with the Buddhist way of training eliminate ‘liberation’ or ‘enlightenment’ or ‘awakening’ or ‘nibbāna’ or ‘arhatship’ or the like from their vocabulary. You hardly need the terms. Once you have any concept of liberation, you will set it as a goal and attach to it. Just do your work, and forget about where to go.

The practical idea of liberation

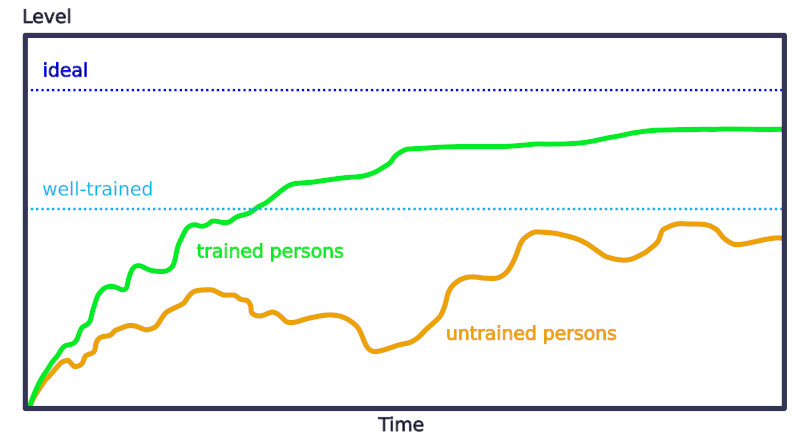

Suggestion in the previous section that practitioners should delete ‘liberation’ and the like from their practical dictionary may make some feel uncomfortable or ungrounded or a little blasphemous. So, I add an illustration of the idea of liberation according to our model, shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Personal development graph

The graph shows unfolding patterns of people. We divide people into two groups here: the trained (green line) and the untrained (orange line). The former is of those who embarks on the path of religious practice, i.e., the self-development according to the Buddhist model (or other similar models). The latter is of the rest, the common worldly people.

The development of the untrained is familiar to most of us. The pattern is highly wavering. Sometimes the life is up (we are happy), sometimes the life is down (we are not happy). At some point we meet a life crisis, at another point we have high exuberance. We learn the life along the way, sometimes successfully, sometimes not. But the level of development normally increases as we grow up, and becomes more stable in the later period of life. Yet, an unexpected downturn of life may be seen.

In contrast, the developmental pattern of the trained is smoother, and it rises up close to the point of the ideal (we may see this as the Buddha line of reference). Once the training is started, the trained ones develop themselves constantly. The life of them can also be up and down because of inevitable vicissitude, but they can handle the hardship properly. So, the trained people are less likely to meet a grave life crisis. They are generally happier and have more enjoyment of their simpler life.

The well-trained line marks the point of no-return. This means once the practitioners reach the point, they are no longer possible to fall back to the pattern of the untrained. Ascending with little wavering is guaranteed. (Some may see this point as the Stream Enterer, but be very careful to use a loaded concept. The point is real, and you can feel it in that way when it comes. But the concept imposed on it is ideology-bound.) The concept of liberation will make the real sense when the practitioners are well-trained enough. And it has no mysterious flavor.

I remember that Alan Watts once said, enlightened, (or ‘well-trained’ in this context), people just feel and act like ordinary ones but 2 inches above the ground. This means they just live a normal life but without any burden and anxiety. This can be a matter of degree, but the feeling is real.

The perfections: model for perfect beings

Rarely associated with the threefold training, the perfections (pāramī) can be likewise seen as a course of training. I bring this into perspective because it really makes sense.

By the traditional account, the perfections are ten qualities leading to Buddhahood. There are many stories related to these qualities told in the Jātakas. The list of the perfections can be found in Buddhavaṃsa and Cariyāpiṭaka, both in Khuddakanikāya. The list, ordered by the appearance of each item in verses, is shown in Table 2.

Table 2: The ten perfections

| 1. |

dāna |

giving, generosity |

| 2. |

sīla |

morality |

| 3. |

nekkhamma |

renunciation |

| 4. |

paññā |

wisdom, understanding |

| 5. |

viriya |

effort, energy |

| 6. |

khanti |

endurance, patience |

| 7. |

sacca |

truthfulness, integrity |

| 8. |

adhiṭṭhāna |

resolution, determination |

| 9. |

mettā |

loving-kindness, friendliness |

| 10. |

upekkhā |

equanimity |

Here are my down-to-earth explanation of perfections.

- Giving is simply the act of giving things away. Another related word is cāga, which often means to sacrifice. It is not dāna commonly known by Buddhists that the giving returns spiritual credit, puñña or merit, to ensure good future life. You give, instead, because others are more needy than you, and you want to make yourself less selfish or greedy.

- Morality is good conduct explained above in terms of not coming from greed, anger, and delusion.

- Renunciation is living the homeless life. This term is straightforward. This is a distinct quality of one who will be a buddha or a great sage. See further discussion in its section below.

- Wisdom is understanding described earlier.

- Effort is simply the energy you run all the perfections.

- Endurance is the quality of withstanding hardship.

- Truthfulness is faithfulness to reality, sincerity or honesty. I would like to add integrity (being firm in moral principles) here, often fashioned as ‘‘Do what you say, and say what you do.’’ The opposite of this is hypocrisy.

- Resolution is the state having firm determination. This is used a lot in meditation. And I make it the most important factor that brings success to our meditation (see A Humble Guide to Meditation).

- Loving-kindness is being kind or friendly to all beings. Technically, this means the intention to make all beings happy. It is logical to also include compassion (karuṇā), the intention to make all beings less suffer, here.

- Equanimity is a subtle quality and has several facets. In general, it means indifference, or having emotional stability, to favorable and unfavorable situations. It can also means keeping oneself composed because nothing better can be done. It can imply a good quality of concentration, because equanimity is one of the jhānic factors.

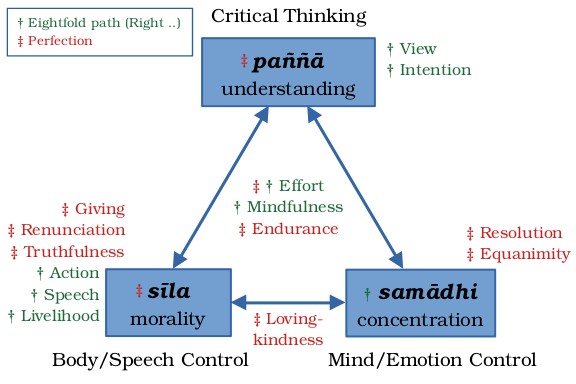

Like the noble eightfold path, each perfection can be put in relation to the threefold training. For some items are redundant, I will leave them out. The full picture of all factors put together is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: The final triangular model with ten perfections

I find it makes sense to put giving, renunciation, truthfulness, and morality itself into sīla category because all these operate in bodily and verbal realms. Resolution and equanimity are best put in samādhi side because they are used mostly here. Loving-kindness straddles both sīla and samādhi because they can be used in both. Endurance is put in the middle because it is commonly used by all parts of training.

Now we get a more elaborate picture of the threefold training that can be applied as a model of self-development. To its best result, we can reach the state of a perfect being according to the Buddhist tenet.

Does wholesome life need renunciation?

As we have seen in the previous section, in the ten perfections the most problematic item is renunciation (nekkhamma). I think it needs a special treatment, so I dedicate the section to this perfection.

This problem is basically ideological one. The main idea is to be a perfectly enlightened being, one has to adopt ascetic lifestyle, being homeless, or exactly without family, spouse and children. This ideology is still upheld firmly in Theravāda traditions.

It is true that ascetic life is essential to the enlightenment of the Buddha, as we know from his story. And the ascetic life is somehow essential to the elimination of suffering as well, as shown by this expression:

sambādho gharāvāso rajopatho, abbhokāso pabbajjā. Nayidaṃ sukaraṃ agāraṃ ajjhāvasatā ekantaparipuṇṇaṃ ekantaparisuddhaṃ saṅkhalikhitaṃ brahmacariyaṃ carituṃ. Yaṃnūnāhaṃ kesamassuṃ ohāretvā kāsāyāni vatthāni acchādetvā agārasmā anagāriyaṃ pabbajeyyaṃ. (D1 191; DN 2)

Being a householder [is] inconvenient; [it is like a] dusty (defiled) path; taking up the ascetic life [is like] an open space. [Being one] living in a house [is] not easy to completely, perfectly like a well-scraped conch, practice the religious life. Indeed, I, cutting down hair and beard, putting on yellow robes, should go forth from home into homelessness. (my translation)

We can say that early Buddhism gave high value to ascetic lifestyle, and it seems inevitable that the Buddha had to establish the ascetic community (the Saṅgha). So, it is logical to have renunciation as a key factor of successful practitioners. But it is too far to say that everyone should be an ascetic from Buddhist ideology.

Now I will fast-forward to our time. Is renunciation still relevant nowadays? As we can see in Buddhist countries, many monks now have a lot of money and use luxurious articles. Their life is far comfortable than many poor people in the country. Many Theravāda monks, except having wife and children, live much like householders nowadays. Will renunciation really help, then?

To make it relevant, we have to reframe the idea of renunciation, and make it applicable to our modern life. For me, renunciation should mean the intention not to indulge in pleasure and comfort. This can be a matter of degree, because living without any pleasure is impossible. Even strict monks enjoy delicious food over bland one, but they do not attach to it. Put it simpler, when you embark on the path of self-development, you have to come out from your comfort zone, sometimes at least.

So, the right approach to renunciation is being aware of what is important and what is not. It is about prioritization. For example, to practice meditation everyday (as suggested in my meditation guide), you have to sacrifice some comfort and enjoyment.

By this view, the answer to the question posed as the topic is certainly ‘No.’ You do not need to give up the world and become an ascetic or a hermit to have a wholesome life. Your wholly happy life can be achieved by practicing the threefold training no matter what lifestyle you live by.

However, as I am a monk myself, I still feel sympathetic to the early idea of renunciation. If we can live our life as socially-sanctioned mendicants, by cutting down our worldly burdens and depending totally on householders, we can get an environment (if managed properly) highly beneficial to our practice. By such an environment, I can produce works as you see here. Look it another way, the contentment of such simplified life is the very result of the practice itself done for a considerable period of time.

Conclusion

If you are a Buddhist uncomfortable with many absurd ideas and practices in the religion, but you do not want to or cannot forsake it anyway. Take the threefold training, together with the eightfold path and the perfections, as your living guideline. Once you adopt the practice (no belief to take for granted here), you can say confidently that you are really Buddhist to its core. And never mind to drop the label ‘Buddhist’ altogether, and take up only the practice. Our goal is not to be categorized as a kind of being. Just a wholly healthy you is fine.

The last caveats: All three folds of the training have to be practice in this very life. Do not develop only morality in this life and postpone concentration to the next, then develop wisdom in another next, otherwise you will miss the whole thing. And the training has to be done throughout your life. Once started, it will be never finished.

The last assertion: The guideline articulated so far is not just a fancy or a thesis proposal. This practical guide can really be done, not so difficult as the tradition puts/stipulates/imagines it, and it has been being done with an affirmative result.

Notes